In January, staff from the WRRB and its project partners met with community members in Wekweètì to share results from last September’s fish camp.

The five-day on-the-land camp was part of the Tłįcho Aquatic Ecosystem Monitoring Program—a community-based project to monitor the water, sediments and fish near Tłįcho communities. Snare Lake is a shallow 40 km long inland lake that forms part of the Snare River watershed that flows into the North Arm of Great Slave Lake. Due to the many historic developments in the Tłįcho region, there are concerns about fish health and water quality. A number of waterways in the region are downstream from mines that used to be in operation or are operating now. Sampling fish and fish habitat will give communities and project partners information that they can use to determine whether fish health, water and sediment quality are changing over time.

An important goal for the project is having monitoring protocols—or procedures—in place that can be used throughout the region. What kind of things do we monitor and how? What are the important indicators that we can use to determine whether fish are healthy and water is clean? From a scientific perspective, the size, age and sex of a fish, and the concentration of various metals and contaminants in its tissues, are some key indicators to measure and monitor. From a Tłįcho perspective, characteristics such as the size, taste and texture of the fish are important to observe in determining whether fish are healthy or detecting any changes.

During the fish monitoring camp, participants are guided by scientific protocols for sampling water, sediments and fish, as well as by the draft Tłįcho Fisheries Health Datasheet (developed through the project in 2011). The Datasheet is based on traditional Tłįcho methods for gathering information on fish condition and observed changes in water quality and quantity.

The idea is to collect ‘baseline’ information on fish populations and habitat as a starting point that can be used to compare with data collected in future monitoring.

Samples can tell us about:

- Water quality. Various characteristics—ranging from the temperature and clarity of the water to the amount of oxygen and nutrients—determine water quality. Natural conditions and human activities can affect water quality which can in turn have an effect on fish and other elements of the aquatic ecosystem.

- The history of what has been in the water in the past. Sediments are debris that flows into a lake and eventually settles to the bottom and builds up in layers. Carried by water or air, they can come from many sources—plant and animal remains, pollen from plants, rock fragments, soil, even charcoal from fires. Sediments pile up year after year, collecting on lake and river bottoms over time. These layers of sediment record events that can be read in the lab and interpreted.

- Fish populations in the area (age, sex, size, general health, life stage).

- Current levels of metals and contaminants in the fish and their environment

- Biodiversity in the aquatic ecosystem –i.e. the variety of species the ecosystem supports. Biodiversity is often used as a measure of ecological health. If the biodiversity is high, with many species present, it usually means that an ecosystem is healthy and relatively undisturbed.

Participants at the Wekweètì fish camp decided to take tissue samples of Lake Trout and Lake Whitefish, both found in Snare Lake and regularly consumed by the community. Elders and community members advised where to set nets to sample different fish habitat, ranging from shallow areas to deeper holes. In total, 80 fish were caught, consisting of four species. The majority of the catch were whitefish (53); the rest were Lake Trout, Round Trout and Northern Pike.

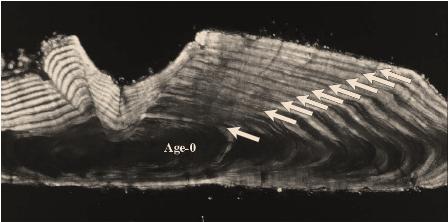

At the camp, elders, youth, fishers and scientists recorded the species and sex of fish caught, measured their length and weight, assessed their health, and dissected fish to examine stomach contents and to extract the otolith (See Photo Gallery below), a small bone in the head, to be used later to determine the age of the fish. It turned out that the oldest fish were a 33-year-old White fish and a 35-year-old Lake Trout. Tissue samples from 40 fish (20 Lake Trout and 20 Whitefish), along with water and sediment samples taken from five locations, were later sent to the Taiga Lab in Yellowknife for analysis.

Based on the analysis of water, sediment samples, and fish tissue, Snare Lake Is considered overall a healthy lake with clean water and healthy fish. We now have a snapshot of conditions that currently exist in the aquatic ecosystem next to Wekweètì. Community members recommended more sampling in the future to see if there are changes over time. The plan for this project is just that: to repeat sampling done at each Tłįcho community every few years, to see, for example, whether metals and other contaminants are increasing over time or are having an impact of fish--and to notice any other changes that may occur in the aquatic ecosystem.

For more information about the Wekweètì fish camp, view the Final Report.

Next Fish Camp is in Gamètì!

-

This June, the project gets underway with a workshop to begin planning this year’s fish camp.

- Later this summer, there will be a second workshop to talk about fish and aquatic ecosystem health--and ways to monitor and measure change. Participants will also identify any concerns the community may have about fish health or water quality--and finalize logistics for the fish camp's location, timing and activities.

- The fish camp will take place at the end of August or early September.

Background: Tłįcho Aquatic Ecosystem Monitoring Program

- The project was launched in 2010 to find out about the health of fish in Marian Lake and the North Arm of Great Slave Lake. It continued in 2011 on Russell Lake near Behchokǫ̀ and last year in Wekweètì.

- The Wek’èezhìı Renewable Resources Board, Tłįcho Government and Wek’èezhìı Land and Water Board work together to implement the project.

- Information collected by the Tłįcho Aquatic Ecosystem Monitoring Project will contribute to a larger picture of the condition and impacts on fish and fish habitat at the watershed scale.

Project Funders:

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans

- Northern Contaminants Program

- Cumulative Impact Monitoring Program

Project Partners:

- Wek’èezhìı Renewable Resources Board

- Tłįcho Government

- Wek’èezhìı Land and Water Board

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans

- Golder Associates

- Health and Social Services (GNWT)

- National Water Research Institute, Environment Canada