WRRB agreed at its last Board meeting in September that it would support proposed changes to harvest regulations to increase harvest of Snow Geese that breed in the western Arctic. Its population was in decline at the beginning of the 20th century, but since then Snow Goose numbers have skyrocketed and their populations have grown to the point that some areas of their tundra nesting habitat are starting to suffer.

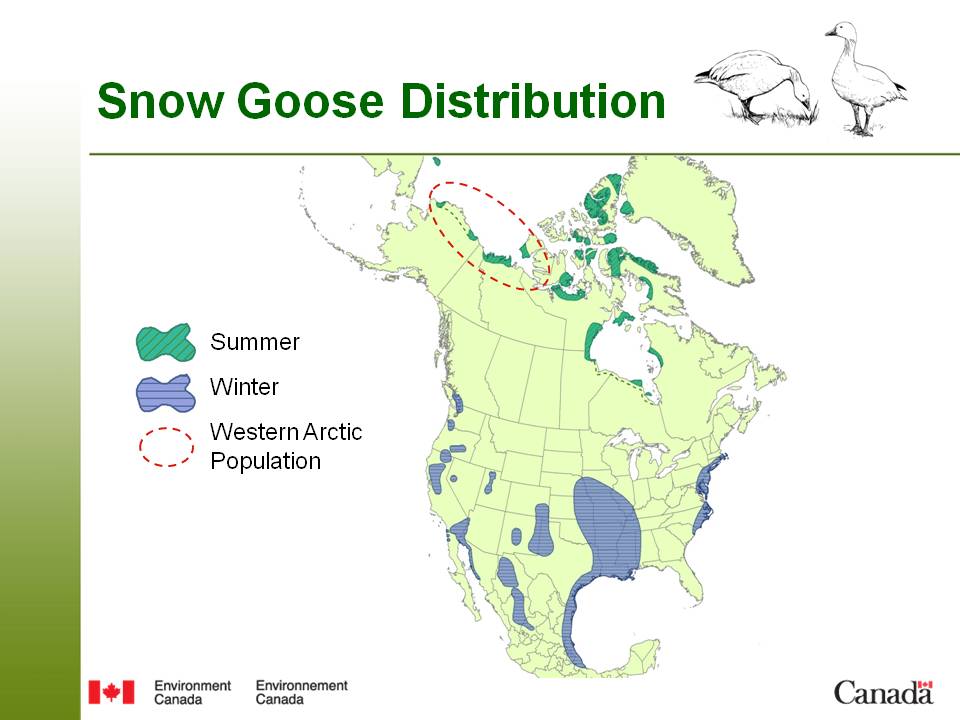

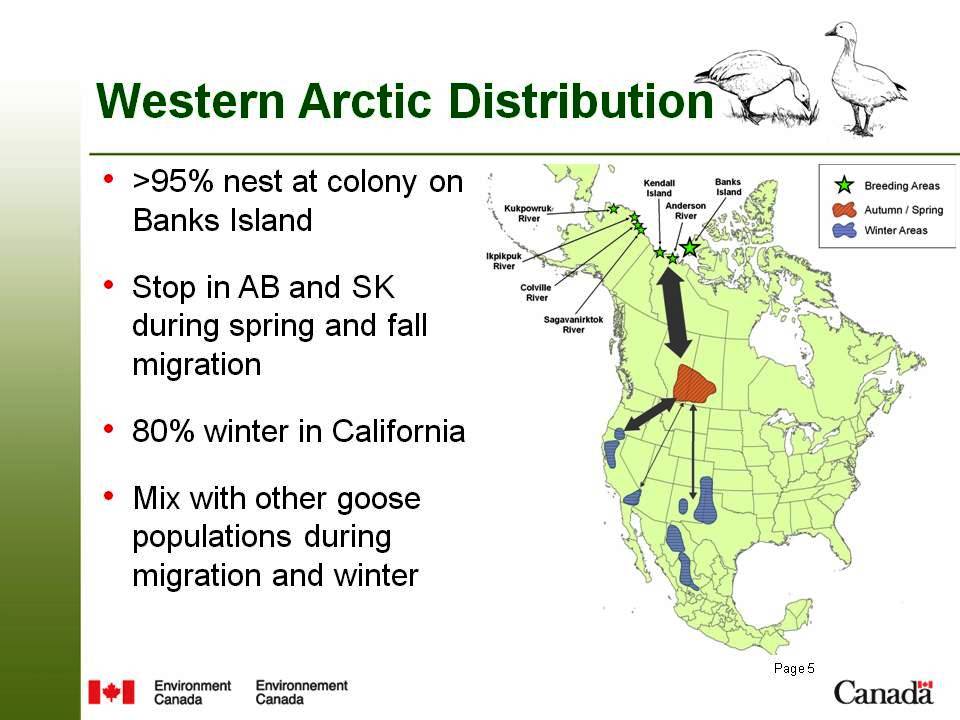

There are two subspecies of Snow Geese. Here, in the NWT, it’s the Lesser Snow Geese that make their way north from wintering grounds in the U.S. and Mexico to nest on the Arctic tundra along the coasts and on islands. Most Snow Geese in the western Arctic nest at a colony and raise their young on Banks Island in the Inuvik region of the NWT, with smaller colonies also at Anderson River and Kendall Island in the NWT, and in Alaska. (See maps in Photo Gallery at the end of the article showing western arctic population seasonal habitat areas. Maps produced by Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service). The other subspecies, the Greater Snow Goose, slightly larger in size, nests in Northeastern Canada.

Snow Geese in the western Arctic are showing similar patterns of rapid population growth that have been seen in other populations of Snow Geese. The breeding population of the Lesser Snow Goose in North America as whole is at a record high—more than 5 million birds. Based on photo surveys of breeding colonies, the number of nesting birds has climbed from 171,000 adults in 1976 to about half a million adults in recent years. That’s more than twice Environment Canada / Canadian Wildlife Service’s (EN/CWS) spring population objective of 200,000 for this population of Snow Geese.

Snow geese descend upon the tundra in thousands to feed upon its grasses, sedges, rushes, shrubs and willows, consuming nearly any part of a plant, including seeds, stems, leaves and roots, and eating plants right down to the ground. There is concern that if the western arctic population of Snow Geese continues to increase, there could be serious habitat loss from their destructive foraging activities. This has been observed elsewhere in the Arctic: habitat loss from overgrazing has occurred in the central and eastern Arctic due to high numbers of Snow Geese. A photo at the end of this article shows the result of overgrazing in one area.

Some localized damage has already occurred on Banks Island from the foraging activities of western Arctic Snow Geese. Loss or degradation of habitat affects other species using the same habitat. Fewer shorebirds, for example, have been seen near the colony and this may in part be attributed to habitat degradation by geese.

Experience has shown that once the population reaches a point where Snow Geese numbers experience runaway growth, it’s difficult to reduce their numbers. Based on CWS’s experience with other goose populations, it is easier to recover goose populations that reach low levels than to reduce them after they experience runaway growth.

If western arctic Snow Geese numbers continue to increase, their numbers may not be able to be controlled through harvest. However, it may be possible to stabilize their numbers if harvest measures are put into place soon.

To that end, CWS submitted a management proposal to the WRRB to increase harvest of the western arctic Snow Geese population. CWS is looking at management options to keep Snow Goose numbers in check by increasing harvest of the Western Arctic population. Proposed management actions include increasing daily bag limits and removing possession limits for the fall sport harvest of Snow Geese in the NWT and Alberta; and opening a spring harvest for non-Aboriginal hunters in the NWT and Alberta. The proposal doesn’t affect the ability of Aboriginal hunters to hunt geese at any time of the year.

Why are Snow Geese populations increasing?

Many biologists think that the changes in their winter feeding ranges and habits might have something to do with it. Traditionally, Snow Geese wintered in coastal marsh areas, feeding on the roots of marsh grasses, but gradually, they have expanded inland to feed in grain fields as well. Abundant forage has likely improved the survival and physical condition of wintering geese, so more geese are returning to the Arctic to breed each spring.

There may be other factors too. Snow Geese nest in remote areas and their breeding colonies have suffered little impact from humans. While eggs and nestlings are at risk from predators such as Arctic foxes, gulls, jaegers, bears, and wolves, adults are generally safe. Their survival is high: approximately 85% of adults survive to the next year. They have a relatively low harvest rate, and most sport hunting of Western Arctic Snow Geese occurs in California, Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Facts about Snow Geese

- The western arctic Snow population of Snow Geese spend more than half a year migrating to and from their spring and summer breeding grounds north of the tree line in Canada and Alaska.

- The birds stop in Alberta and Saskatchewan during spring and fall migration.

- About 80% of the population currently winter in California. Some birds also winter in parts of New Mexico, Texas, Colorado and Mexico.

- Winter numbers have also greatly increased. About 800,000 Snow Geese were estimated to be present during the California winter surveys in 2011.

- Snow Geese breed from late May to mid-August One of the common words used to describe a group of Snow Geese is a “blizzard” –an apt word to describe the tens of thousands of geese that take to the sky during their spring and fall migrations. Flocks of several thousands –resembling a blanket of snow--can also be seen feeding in fields or marshes on their winter ranges.

- Snow geese are strong fliers, walkers and swimmers.

- During migration, Snow Geese fly so high they can barely be seen. Rather than flying in “V” formations like Canada Geese, Snow Geese form shifting arcs as they fly along narrow flight corridors from traditional wintering areas to the tundra.

- On their wintering grounds, the geese feed on grasses, water plants and grain left in fields. By spring, they have to fatten up for the long flight to their nesting grounds in the Arctic—a journey of almost 5000 kilometres.

- The young feed themselves, but are protected by both parents. Within 3 weeks of hatching, goslings may walk up to 80 km with their parents from the nest to a more suitable brood-rearing area.

- After 42 to 50 days, they can fly, but remain with their family until they are 2 to 3 years old.