To sit down with fish biologist Paul Vecsei is to discover so many new ways to see fish –and to catch at least a little of his passion.

A fish biologist with Golder Associates, Paul has participated in each fish and water monitoring camp since the Tłı̨chǫ Aquatic Ecosystem Program began in 2010. His fascination with all things fish started when he was kid who liked dinosaurs and then became interested in fish. To Paul, fish resembled those prehistoric giants—and were equally as mysterious. “It was fascinating that you could interact with this world of creatures, and the fact that under water was another world, just added to the mystery,” he says.

Eventually that interest brought him north which he calls a last frontier when it comes to studying fish. He’s interested in exploratory ichthyology, the scientific study of fish, and here in the North, he is able to study new species and “morphs” within species that haven’t been observed or may not have been documented elsewhere.

“Great Slave Lake is a relatively pristine system on an ecosystem level, ecologically and environmentally,” he says and points to one particular species, Ciscoes. “Every niche that can be occupied by them is occupied,” and that has resulted in great diversity within the species and “an array of radical morphologies”. Ciscoes may vary in the shape of their mouths or the size of their eyes, for example, but it’s their gill rakers that are the most significant distinguishing feature because they can vary in their number and length. Gill rakers are small comb-like bones that help a fish take in more oxygen from the water. They also help filter feeders like Ciscoes that feed on small creatures like shrimp by straining larger particles in the water.

Drawing Art and Science Together

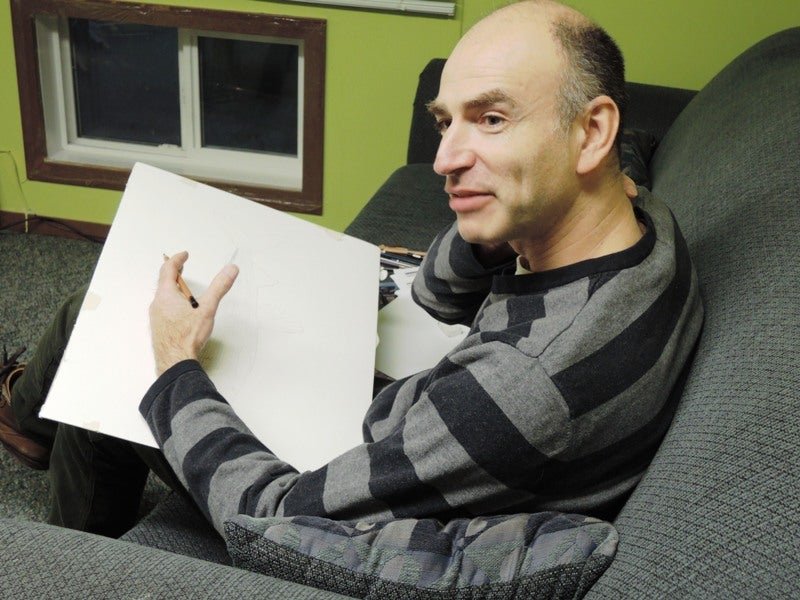

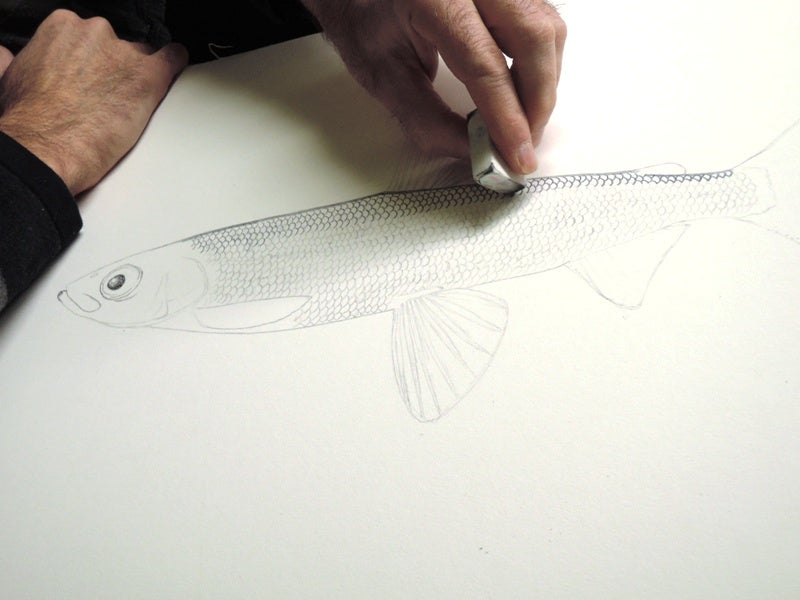

Scientific illustration is a tool that Paul uses to provide information about various fish species. The task of the scientific illustrator is to prepare accurate renderings of scientific subjects –like fish—to inform and explain. Proportions, colouration and anatomy all must be portrayed accurately in a two-dimensional drawing. The illustrator has to know his subject so that the illustration appears life like and natural. But it must also be aesthetic. Paul renders his subjects in pencil, watercolour washes and layers of pencil crayon to create beautiful, intricately detailed portraits. Striving for absolute representational accuracy is an involved and often “daunting” task, he says.

Understanding Fish Through the Lens of a Camera

When he’s not drawing or studying fish, he’s often photographing them in their natural habitat. He’s one of a very few who photograph northern fish under water. Photography is a useful tool for classifying and describing fish, but it also gives his viewers an intriguing window into a world not many of us see with our own eyes. Paul’s underwater photos show us what a fish might see. Many are taken with a fish eye lens that brings elements of the scene together in striking ways. One photo, for example, shows both life above the water’s surface and fish swimming beneath—a perspective that a fish might have looking up at the shore.

His favourite fish photo is one of a pod of Ciscoes that made National Geographic’s Photo of the Day. It was a rainy fall afternoon where everything came together for a moment. Whitefish and Ciscoes were swimming in formation and Paul still remembers the arc beam of light that appeared and that he captured in the photo.

Underwater photography in the North has its challenges, though. “Depending on the time and weather, it can be dangerous and cold, and you can hardly concentrate on the photography, “ he notes, adding that there are currents, open water and water so cold it’s “liquid ice”, remembering a snorkeling expedition at Bluefish Lake when he dove into minus 5 degree Celsius water, wearing a dry suit and a snowsuit underneath.

So what can a scientific illustration tell us that a photograph can’t do as well, and vice-versa?

“A scientific illustration is a cleaned up photo, “ Paul explains, “that places emphasis on the traits or characteristics peculiar to that species.” An illustration can make it easier for the viewer to understand the subject because extra detail is removed and relationships between structures are more apparent than in a photo.

A photograph, on the other hand, portrays the subject in the context of its environment. A camera lens will pull in “the blue of the sky or the refection of the water and that will have an influence on the visual rendering of that fish.” It’s an interesting insight. Take a look a photograph Paul has taken of an Arctic Grayling and compare it with his illustration in our Photo Gallery at the end of the article. The photo shows the iridescence in the Grayling’s dorsal fin lit up in a shaft of light that’s penetrated into the water’s depth. While some parts of the fish are illuminated, others are in shadow, as they would be seen in real life—and we take a wider view, seeing the fish in its habitat. In his illustration of an Arctic Grayling, minute details –scales, ridges and lines, fins, and eyes—are highlighted and the subtlety of the fish’s colouration is suggested through shading and watercolour washes.

Here are some of Paul's photos --and a link to his online Gallery to view more.