They provide important ground cover for the northern boreal forest floor and brighten the winter landscape with splashes of colour against exposed rock. By interacting with bare rocks and breaking them down, and by trapping organic matter from the air, they often start to create and enrich soil where other plants can eventually grow. In winter, they are the principal food for both Tǫdzi (Boreal caribou) and Ekwǫ̀ (Barrenground caribou) on their wintering ranges. Small and intricate in form, they are amazingly tough and can thrive in the most extreme Arctic environments. In fact, researchers have taken some species into space to test their toughness --and they survived. They are Ɂadzìì, lichen, and they are a fascinating feature on the landscapes of Wek’èezhìı and throughout the North.

Caribou eat different plants during the year that include grasses, sedges, birch and willow leaves, and mosses, but during the winter months they depend on Ɂadzìì. Relatively high in energy-rich carbohydrates, Ɂadzìì provide caribou with energy to make body heat, especially important in winter. Caribou have an amazing ability to smell Ɂadzìì under the snow reportedly as deep as 70 cm. Using enzymes produced in their stomachs, they are able to break down Ɂadzìì ’s nutrients into sugars they need for energy in winter. Bison in the NWT have also been observed feeding heavily on Ɂadzìì in the fall when they move from meadow habitats into the forests.

“Reindeer lichen”, belonging to the Cladonia family, are important forage for caribou. An ongoing Tłı̨chǫ knowledge project has been collecting information on the vegetation that tǫdzi prefer as part of a study to monitor the state of tǫdzi habitat and document when caribou return to burn areas. Community researchers have identified many kinds of plants that caribou feed on. Caribou forage on both ground lichen such as Adzı̀ı̀ degoo (white lichen), Ɂadzìì dɂekwo ̀ (yellow lichen), and Ɂadzìì dezǫ (black lichen)—and tree lichen (Daàghǫǫ).

Grey Reindeer Lichen (Photo: Susan Beaumont, WRRB)

Grey Reindeer Lichens (Cladonia rangifera) are one of the Ɂadzìì that are most frequently grazed by caribou. In fact, their scientific name includes the word “rangifer” which means “caribou”. Their appearance is striking with greyish-white intricate “branches” that resemble caribou antlers. These Ɂadzìì form extensive carpets on the ground in open coniferous forest to the tundra. Green Reindeer Lichen (Cladonia mitis) is similar in appearance but light green in colour. Tree Reindeer Lichen (Cladonia arbuscula) is also similar and is a close relative. Northern Reindeer Lichen (Cladonia stellaris) or Star Reindeer Lichen grows in round clumps often in thick, extensive mats on the ground. It’s noticeable for its bunchy appearance with its many yellow-green “branches”, each branch ending in a star-shaped whorl of branchlets. Its surface dries quickly, forming a crunchy upper layer but below this the Ɂadzìì can remain moist for long periods.

Green Reindeer Lichen (Photo: Susan Beaumont, WRRB)

Northern Reindeer Lichen, also known as Star Reindeer Lichen with Bearberry plants in fall (Photo: Susan Beaumont, WRRB)

What are Ɂadzìì (Lichen)?

Besides providing a key food source for caribou, Ɂadzìì are an intriguing part of the northern boreal ecosystem. They are specialists in living where few or no other living things can: on unlikely surfaces such as tree bark; thin, bare soil; animal bones; dead wood; or exposed rocks. They need very little to live on: light, moisture, and a place to anchor. They can take moisture and minerals directly out of the air and because they don’t need roots to collect water and nutrients from soil, they’re free to grow almost anywhere including on hard surfaces like rock. Many can make food when the temperature gets very low and when there is little light, and many, like Grey Reindeer Lichen, can survive long periods of time without water. When light or moisture becomes scarce, many Ɂadzìì go into survival mode and shut down most of their life functions until conditions improve. How are Ɂadzìì able to do this? It all has to do with partnership.

Although they are often called “caribou moss” or “reindeer moss”, Ɂadzìì are in fact not moss -–tiny plants with stems and leaves—but are something very different. Ɂadzìì is not a single organism, but two: a fungus and an alga which live and grow together in a relationship that benefits both. What’s in it for each of them in this relationship? The relationship between the fungi and the algae that make up Ɂadzìì is not fully understood but some features can be observed. The fungus part provides an anchor and protection against the elements. It provides structure and in most cases, forms the shape of the Ɂadzìì. To the algae, water is essential for life and reproduction, and fungi are great water gatherers. The fungus catches and stores water, keeping the algae from drying out, and it provides nutrients that it absorbs from the substrate –the surface --it grows on. For its part, the alga, safely encased in the fungus body, is able to manufacture the food that it needs to exist and sustain itself in that habitat--and provide food for the fungus.

Most Ɂadzìì grow very slowly. How do they reproduce? Most are very brittle when they’re in their dry, crunchy state during dormant periods when they "turn off". Many depend on just plain breakage to reproduce “vegetatively”. A broken piece in the right conditions and on favourable habitat can start an entirely new Ɂadzìì colony. Rain, caribou foraging and trampling activity can break and damage Ɂadzìì. Fragments can be blown around by wind, washed along by water, or carried off as passengers on insects or birds. Other Ɂadzìì fungi make spores to form a new Ɂadzìì. After they germinate, they need to capture new partners!

Some Other Common Lichens in Wek’èezhìı

Ɂadzìì come in a variety of sizes, shapes, colours and textures. Some are crust-like and are closely attached to rocks or tree trunks. These often colourful Ɂadzìì are aptly named crustose lichens. Foliose lichens are leaflike and are only partially attached to a surface. Fruticose or shrubby lichens are made up of tiny branches and are free-standing -- either upright or hanging from a surface. The reindeer lichen fall into this category.

You may have noticed the scarlet red of Cladonia borealis (Boreal Pixie Cups) scattered across the forest floor and on decaying conifer logs. They are often found close to another showy forest lichen sporting scarlet colours, “British soldier” lichen (Cladonia cristatella). These tiny, red-capped Ɂadzìì recall the red uniforms of British soldiers stationed in Canada some 200 years ago. Take a look at our Photo Gallery at the end of this article for a closer look at these elfin lichen in their miniature wonderland on the forest floor.

Red Soldier Lichen, Rosette Pixie Cup lichen and other lichens on an elfin-like forest floor (Photo: Susan Beaumont, WRRB)

Elegant Sunburst Lichen (Xanthoria elegans) or Rock Orange Lichen forms bright splashes of orange on rock faces, often where raptors like Peregrine Falcons roost or nest. Biologists have used those patches of colour to locate the roosts and nest sites of raptors. Bird droppings contain high levels of nitrogen, and these Ɂadzìì like nitrogen-rich environments. They are one of the species that scientists took with them to the International Space Station where this hardyɁadzìì withstood the harsh conditions of space!

Peregrine Falcon in flight next to rock face encrusted with Elegant Sunburst Lichen (Photo: Gordon Court)

Dahghaà in Tłı̨chǫ refers to “black hairy lichen on trees”. Old Man’s Beard Lichen (Usnea hirta) is a type of tree lichen that grows in thick tufts like a beard on the bark and lower branches of conifers like spruce and tamarack.

Adzı̀ı̀ degoo (tree lichen) (Photo: Allice Legat)

Did You Know?

- Reindeer lichens are slow growing and long lived. Grey Reindeer Lichen generally produce a new branch each year, so the age of a clump can be estimated by counting back through the major branching along a stem. Mature clumps of these lichen are often 100 years old or older.

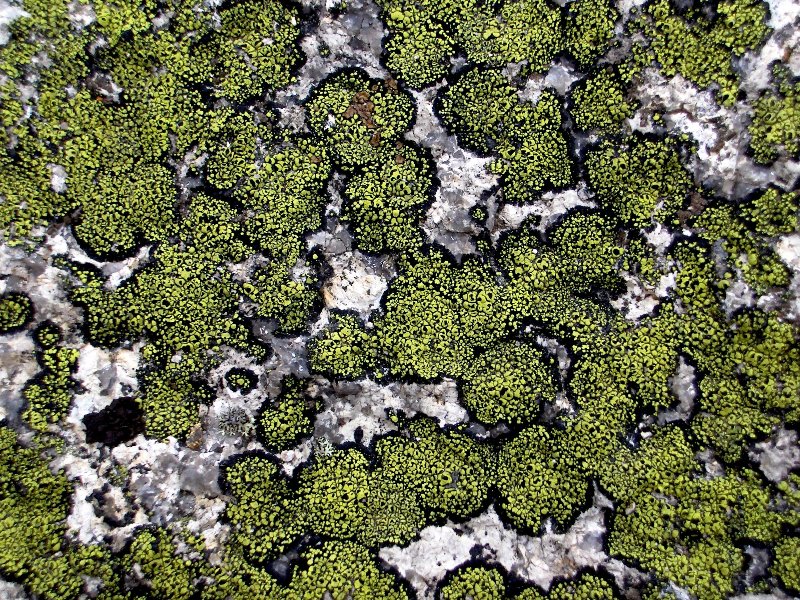

- Left undisturbed and unchallenged, some Ɂadzìì are very long-lived. A crustose lichen found on exposed rock faces, Rhisocarpon geographicum, commonly known as "Map Lichen", is particulary long living. In fact, lichens with known, slow growth rates like this lichen have been used to date exposed rock and other surfaces. This process, known as lichenometry, has also been used to estimate the dates of geological events such as the retreat of glaciers. Since the lichen only grows at a fraction of a millimetre each year, lichenometrists can use its size to date whatever surface it's growing on.

- Rhisocarpon geographicum is often called Map Lichen because it grows in patches bordered by black lines and, as a result, looks like a map with little rivers and roads. Researchers took a colony of this extremely tough Ɂadzìì into Earth's orbit where it was exposed to empty space for nearly 15 days --and survived.

- Some species of birds such as the Common Merganser, Boreal Chickadee and the Rusty Blackbird use Ɂadzìì materials in constructing their nests. One reason for using Ɂadzìì might be to benefit from the Ɂadzìì’'s insulating properties. Some birds may even seek Ɂadzìì out for camouflage. Ɂadzìì are a key element in the food chain of the boreal owl. Voles, for example, consume Ɂadzìì and are an important prey species of the boreal owl.

Map Lichen (Photo: Creative Commons)

Lichen on taiga forest floor near Whatì (Photo: Susan Beaumont, WRRB)

![Elegant Sunburst Lichen (Photo: By Björn S... [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons)](/sites/default/files/Elegant_Sunburst_Lichen_-_Xanthoria_elegans_%2816802028691%29%20CC_website.jpg)

Elegant Sunburst Lichen (Photo: By Björn S... [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons)