In April 2016, results from last September’s fish camp on Russell Lake were shared with community members at a presentation in Behchokǫ̀. The workshop was a great opportunity to discuss the aquatic health of their community—and there’s good news. None of the results from the fish, water and sediments that were sampled last fall were considered to be abnormal, and as a result, there were no health concerns. Overall, the results suggest that fish and their habitat in Russell and Slemon Lakes are in good shape. Comparing the 2015 results with the results from the sampling that was first done in the area in 2011 as part of the Tłı̨chǫ Aquatic Ecosystem Monitoring Program (TAEMP), there appears to have been no appreciable changes in the fish, water or sediments.

What is the fish habitat like in the Russell Lake area?

Fisheries biologist Paul Vecsei, Golder Associates Ltd., started the presentation off with a description of the unique characteristics of Russell Lake and how they influence the kinds of fish found there. Russell Lake is a shallow, turbid (cloudy due to suspended particles) lake with numerous islands and weedy bays. The 42 km long, inland lake is “an interesting lake because it’s connected to Marian Lake, which in turn flows into the North Arm of Great Slave Lake,” Paul said.

Its shallow bays provide essential habitat such as nursery habitat for different life stages of several fish species. Although primarily made up of warm water species like Ehts'ę̀ę / Ehch'ę̀ę (Walleye or Pickerel), Dehdoo (Suckers) and Įhdaa (Northern Pike or Jackfish), the fish community also includes cold water species such as Łıh (Lake Whitefish) and Łıwezǫǫ̀ (Lake Trout). “We know if we net fish, we’re likely to get Coney, Jackfish, and Whitefish”, he added, noting that “Lake Trout is rare” in this habitat. “You have to keep in mind that Russell Lake is ‘marginal’ habitat for Lake Trout. That means it’s not the ideal habitat these fish prefer and thrive in. It is primarily a Whitefish, Jackfish and Coney Lake.”

Another factor to consider, Paul explained, is that there are years when there may be a cooling or warming trend. “If the water is too warm in summer, they leave and are not using the lake as much.” Fish adapt and the fish community that are present –the different species of fish—can change naturally. “That’s not good or bad necessarily,” Paul said, “but it shows how sensitive they are to environmental changes.”

Russell Lake is similar to Marian Lake in its southern portion, Paul explained, but becomes clearer the further north you go. That in turn, can affect which species are present –or absent. For example, predatory fish like ı̨hdaa are “sight feeders”, relying on their keen eyesight to spot and ambush their prey. And Russell Lake is not the same where it joins Marian Lake compared with where it joins Slemon Lake. Different species of fish have different habitat requirements and will likely be found in some locations and not others.

Fish Camp 2015 Photo: Paul Vecsei, Golder Associates Ltd.

What did the TAEMP team learn from the fish samples?

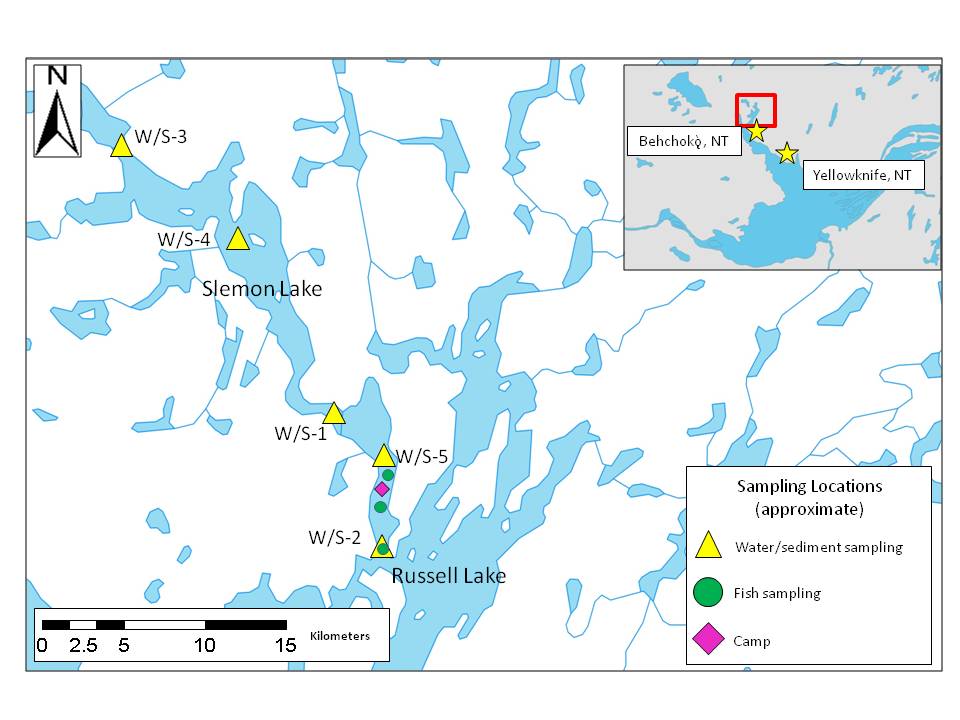

Youth, elders, community members and scientists were at camp on Russell Lake from September 14-18, 2015 to sample fish, water and sediment in Russell Lake and Slemon Lake, at the same camp location that was used in 2011. Using gillnets at several locations in Russell Lake, fish camp participants visited similar sampling sites as those fished in 2011. (See map of sampling locations) These sites represented a variety of habitats, ranging from shallow weedy areas to deep holes with no aquatic vegetation.

Behchokǫ̀ Fish, Water and Sediment Sampling Locations 2015. Map: WRRB

Water and sediment samples were also collected, with sampling locations located as close as possible to 2011 locations. Windy conditions, low water levels and thick aquatic vegetation made it difficult to place some of the comparative sampling exactly where the 2011 sampling sites had been located.

Five species of fish were caught on Russell Lake, including ehts’ę̀ę and ı̨hdaa representing the common top predators, and łih representing “benthic invertebrate feeders” –fish that feed off or near the bottom of the lake where tiny fish, snails and insects can be found. Of the 78 fish that were caught, there were 4 Wıìle (Inconnu), 43 łih, 11 ehts’ę̀ę, 1 Kwìezhìı (White sucker), and 19 ı̨hdaa. The four wıìle, likely from Marian Lake, use nutrient-rich Russell Lake for feeding, and not spawning, Paul noted. Russell Lake appears to act like a nursery for young wıìle. “The lake warms up fast and has little fish for coney to eat. They use it to live and grow, “Paul explained. “When it’s time to spawn, they go up to Marian Lake to Marian River.”

Pickerel have a spawning area in the northern part of the lake. “Not every lake has pickerel—it’s a unique and precious resource,” Paul said. Aside from its food value, this fish could act as an indicator of the health of the lake itself. “This is something to watch,” Paul said. “If they go, then what’s happening?”

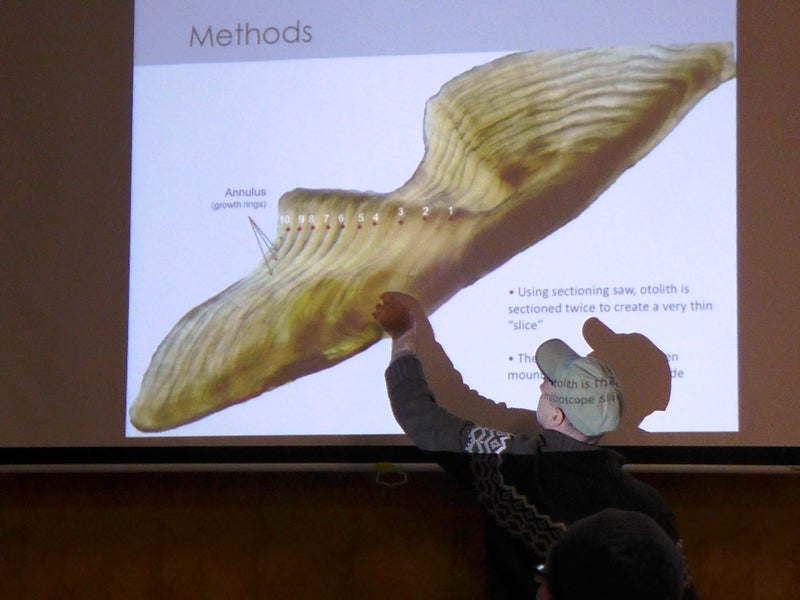

At fish camp, the fish were measured and weighed and observations were made on the overall health of each fish. The sex and stage of maturity were also recorded, observing whether a particular fish would be spawning in the fall, or, in the case of an ı̨hdaa, in spring. Tissue samples were collected from 11 ehts'ę̀ę, 17 ı̨hdaa, and 20 łih to test for mercury concentrations, as well as concentrations of other metals. Paul also removed a tiny bone known as the otolith from the head of each of the sampled ehts'ę̀ę and łih. Biologists can estimate a fish’s age by counting the rings that can be seen when the otoliths are viewed under a microscope, similar to counting the annual growth rings in a tree.

Paul Vecsei removing an otolith, a tiny bone in a fish's head, that will be used to estimate the age of the fish. Photo: Boyan Tracz, WRRB

Paul Vecsei showing a photo of an otolith that has been sectioned under a microscope so that rings are visible. These rings can then be counted to estimate the age of the fish. (Photo: Susan Beaumont, WRRB)

The ı̨hdaa were aged using a slightly different method. A large bone called a cleithrum is used instead of the otolith. Located under the gill flap, a new layer is added to the bone each year, much like the growth rings of a tree. Cleithra are thought to be a reliable, accurate method to estimate the age of ı̨hdaa, and it is easier to extract the bone and see its rings without using a microscope. Some very old ı̨hdaa were caught at the 2011 fish camp; two fish were 20 years in age and one was 21. The oldest fish caught at this fish camp (2015) was a 24-year-old łih.

Paul Vecsei holding up a cleithrum - a bone that's used in aging ı̨hdaa (Northern Pike) Photo: Meghan Schnurr, Wek’èezhìı Land and Water Board

Knowing the ages of the fish helps biologists understand the growth rate of the fish and whether they are growing at the rate normally expected for a certain age of fish. “Imagine if all the pickerel at 10 years in age were half the size they were supposed to be. It would mean they are under stress. Maybe there’s not enough food, for example. Something’s wrong,” Paul said. “This is one of the ways we can tell if fish are healthy.”

Mercury is known to naturally occur in small amounts in lakes throughout the North. Mercury levels are generally lower in species like łih which feed on aquatic insects and other organisms near the bottom of the food chain. Levels are usually higher in predatory species such as ı̨hdaa because they are more likely to eat smaller fish and mercury becomes more concentrated with each step up the food chain. Fish that eat other fish may have higher levels of mercury due to biomagnification. Larger, older fish may also have higher levels of mercury because they have been exposed to it for longer. This is called bioaccumulation. As expected, the sample results showed very low mercury levels in (łih). Though ı̨hdaa and ehts’ę̀ę were found to have higher mercury levels than łih, this was not unexpected given that they are predatory fish which commonly exhibit higher levels. Even these larger predators’ mercury levels were lower than what Paul has seen for other lakes and “lower than some very remote lakes we’ll never set foot on.”

Mercury levels in fish can change over time, Paul said. Those changes can be the result of natural changes like global warming or a climate trend, for example. “A cycle of warmer years can cause more mercury to be available in a system, and mercury can increase from that.” Or industry, such as mining, can cause an increase in mercury in the environment. Future sampling will provide further indications of any changes in mercury levels over time.

What did the Test Results Show for Water and Sediments?

Youth learned how to take water and sediment samples. Photo: Roberta Judas, Wek’èezhìı Land and Water Board

Under supervision, youth helped collect water and sediment samples at five locations selected by community members in 2011. In general, water and sediment quality of Slemon and Russell Lakes is good. Results from the 2015 TAEMP are very similar to results from the 2011 TAEMP. There was no apparent change in the water quality and sediment quality between 2011 and 2015. Some variation is to be expected with varying natural conditions and the relatively small sample size.

Nicole Dion, Aquatic Quality Scientist, GNWT, and Sean Richardson, Wildlife Coordinator,Tłı̨chǫ Government, talked about the water and sediment sampling. Nicole presented the lab results and Sean described the field conditions and field sampling.

Nicole was at the 2011 camp and described how the elders chose the original sampling sites –selecting water as it flowed into the lake and through the system. Sample locations were arranged from those more upstream (Slemon Lake, W/S-3) to downstream (Russell Lake, W/S-2). W/S-3 was located at the mouth of Snare River flowing into Slemon Lake; W/S-4 was in the middle of Slemon Lake, and W/S-2 was at the mouth of the channel flowing into Russell Lake. (See map)

Water:

Water sample results indicated that most metal concentrations in Slemon Lake and Russell Lake were very low. Many results were found to be below Minimum Detection Levels, with only Aluminum and Iron found to be outside some of the guidelines. Similar to results in 2011, the 2015 total aluminum concentration was the lowest where the water flows into Slemon Lake (W/S-3), and concentration increased downstream with the highest level found at the site furthest downstream. Similar to the pattern observed with aluminum, results in 2011 and 2015 showed total iron concentration was the lowest at site W/S-3 (upstream) and highest at W/S-2 (downstream).

The higher concentration of aluminum and iron may be due to disturbance of the sediment as a result of fishing in the area. Poles placed in the sediment to support fish nets likely rotate and “churn” the sediment. Windy conditions can also result in additional mixing of water and sediment. Aluminum is one of the most abundant metals in the environment. Sediment is rich in aluminum, and wind can stir up the water, pushing up sediment from the bottom of the lake. “The lake is shallow this year,” Nicole said, “picking up aluminum as the water flows through the system and further downstream.”

Sediments:

Sediments accumulate and transform fine materials, organic matter, and the remains of aquatic vegetation and organisms. Physical and chemical processes at the water and sediment “interface” (where water and sediment meet) can considerably influence water quality in water bodies. Lake sediment analyses can provide an indication of the water quality because many contaminants, such as metals and trace organic contaminants, are bound to or are incorporated with sediments. Locations are chosen and water and sediment samples analyzed in the hopes of having a good representation of the aquatic environment and the living conditions for the fish population in the area.

Most metals concentrations found in the 2015 sediment samples were similar to the results seen in the 2011 samples, with sediment samples showing elevated concentrations. However, elevated levels found in the sediment did not appear to be affecting the water quality.

***

Narcisse Chocolate speaking at the fish camp results meeting in Behchokǫ̀ Photo: Susan Beaumont, WRRB

At the end of the presentation, community members expressed their support of the TAEMP and hearing the sampling results. Narcisse Chocolate said, “I learned a lot from my grandfather. I learned from him and I sell fish. It’s good to hear this. You guys are doing a good job.” Paul commented on the contributions that community members have made to the success of the TAEMP. He spoke how the fish camps are a “good forum for the exchange of ideas and learning together”. At each fish camp, elders have shared their traditional knowledge of fish and fish habitat, and showed youth various techniques for preparing fish. Their demonstrations show their “skill and precision gained over many years of practice,” Paul said. Paul also looked forward to future fish camps: “The communities are understanding the sampling procedures, so next year one of the younger kids will do up the fish around the processing table and show us how it’s done!”

Processing fish to take tissue and otolith samples. Photo: Boyan Tracz, WRRB

Fact Box: TAEMP

- Last September 2015, the Tłı̨chǫ Aquatic Ecosystem Monitoring Program (TAEMP) returned to Behchokǫ̀ where TAEMP first started.

- In 2010, a pilot fish camp was set up at a traditional fish harvesting site on an island in Marian Lake, focused primarily on sampling fish. The following year, a camp was held on Russell Lake and the program was expanded to include water and sediment sampling. Since then, the program has grown to its current form: a community-based program using science-based sampling methods to monitor fish and their habitat near each of the four Tłı̨chǫ communities.

- With baseline sampling completed near all Tłı̨chǫ communities, TAEMP is now in the second phase of the program, which involves returning to lakes sampled four years earlier and repeating sampling to see if there have been any changes in that time. The 2015 Behchokǫ̀ fish camp began this next phase of comparative sampling, part of a four-year monitoring cycle.

Fact Box: Fish, Water and Sediments

- The Department of Health and Social Services, GNWT, has prepared a fact sheet on the health effects of mercury in fish and a traditional food fact sheet on country foods. Both, along with other information, are available on the Health and Social Services website at www.hss.gov.nt.ca or check out the links.

- Various characteristics—ranging from the temperature and clarity of the water to the amount of oxygen and nutrients—determine water quality. Natural conditions and human activities can affect water quality which in turn can have an effect on fish and other elements of the aquatic ecosystem.

- Sediments are debris that flows into a lake and eventually settles to the bottom and builds up in layers. Carried by water or air, they can come from many sources—plant and animal remains, pollen from plants, rock fragments, even charcoal from fires. Sediments pile up year after year, collecting on lake and river bottoms over time.