Common Nighthawk and Olive-sided Flycatcher

In November, the WRRB supported posting the proposed draft Recovery Strategy documents for the Common Nighthawk and the Olive-Sided Flycatcher. The Recovery documents will be posted to the Species at Risk Registry for a 60-day public comment period. Both migratory bird species were listed as Threatened under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA) in 2010. In July, the WRRB agreed to support the draft Recovery Strategies for these species at risk. You can read more about the Common Nighthawk and the Olive-sided Flycatcher and some of the threats each species faces here.

Peregrine Falcon

The WRRB also supported posting the draft management plan for the Peregrine Falcon to the Species at risk Registry for a 60-day public comment period. The Peregrine Falcon was listed as a species of Special Concern under the federal SARA in 2012.

In the 1960s-70s, this bird suffered a dramatic decline in numbers, mainly because of widespread use of pesticides such as DDT. Pesticides “bioaccumulated” –or gradually built up—in females and caused their eggshells to thin, preventing their offspring from developing. However, Peregrine Falcon numbers have been increasing since the 1970s due to a North American ban on DDT and related pesticides, as well as recovery efforts such as the re-introduction of falcons in southern Canada. Pesticides are still used in the birds’ wintering grounds, and are still found in Peregrine Falcons, but not enough to significantly affect reproduction.

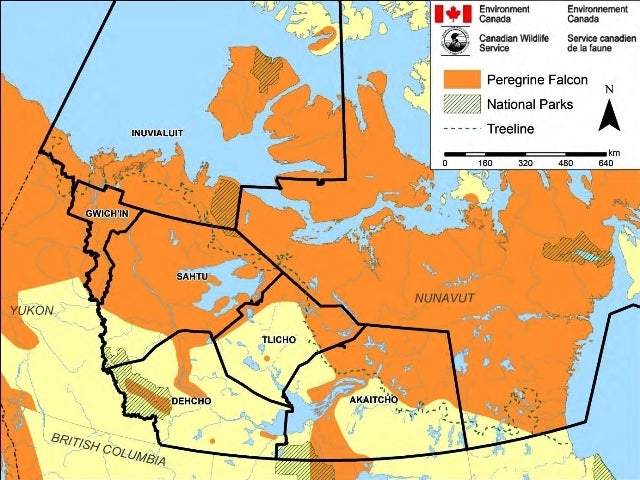

The map in the Photo Gallery at the end of this article shows the Peregrine Falcon's range in the NWT. These birds arrive at their breeding areas in the North, including the northern and northeastern part of Wek’èezhìı, in May. In October, they leave for their wintering grounds in southern Canada and into South America.

Fact Box

- Peregrine Falcons are large, quick predatory raptors. Their average cruising flight speed is 40-55 km / hr, reaching speeds of up to 112 km / hr in pursuit of prey. When dropping on prey with their wings closed and dropping from heights of more than 1 km, it’s been calculated they can achieve speeds of 320 km / hr.

- Their strong, sharp yellow talons allow Peregrine Falcons to capture other birds, even in flight.

- Female Peregrine Falcons are larger and heavier than males.

Red-necked Phalarope

The WRRB reviewed the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) 2-month interim status report for the Red-necked Phalarope, a small migratory shorebird. The WRRB agreed to support a recommendation for a national designation as a Species of Special Concern. This species appears to have declined over the last 40 years, but because it breeds in remote areas and winters at sea, its population status is difficult to monitor and assess.

Each summer, the Red-necked Phalarope makes its way north to breeding grounds on the tundra and subarctic lowlands in the NWT and other parts of northern Canada. Shallow freshwater ponds provide important feeding areas, particularly for females that must build energy for egg production and for the young which need to gain weight rapidly to prepare for their long-distance migration to overwintering areas in South America. But warming temperatures appear to be posing a threat to this important habitat, resulting in shrub vegetation moving northwards and the drying of wetlands.

The Red-necked Phalarope may also face threats during migration and over-wintering. Changes in the marine environment, for example, may affect the abundance or availability of the Red-necked Phalaropes’ preferred prey: copepods, tiny aquatic animals related to crayfish and water fleas.

Fact Box:

- Red-necked Phalaropes appear to have a unique way to catch prey. They will often swim in a small, rapid circle, forming a small whirlpool. This spinning behaviour is thought to aid feeding by raising food from the bottom of shallow water. The Red-necked Phalarope then reaches into the centre of the vortex with its slender, straight bill, plucking small insects or crustaceans like copepods from the water.

- Females are larger and more brightly coloured than males. In an interesting role reversal, males incubate the eggs and rear the chicks! It’s the females that leave first to begin their southward migration, leaving the males to incubate and look after the young.